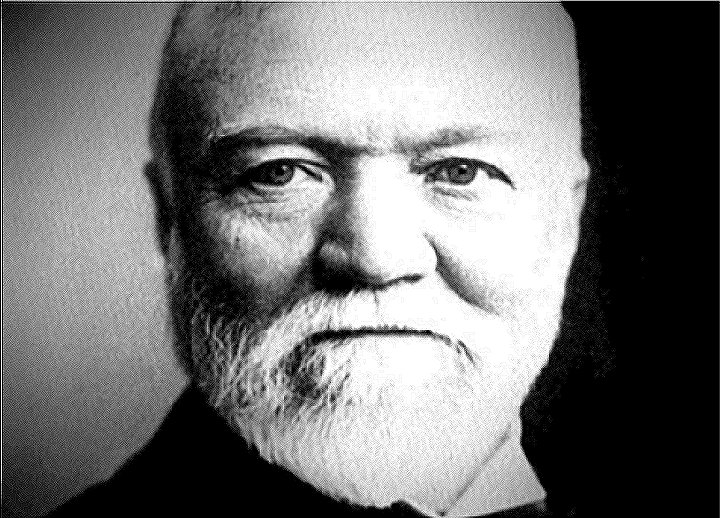

Andrew Carnegie:

Never Knowing Fatigue

By Harold Frost

Biography magazine, 2001

Born in Scotland on November 25, 1835, Andrew Carnegie was the son of William Carnegie, a weaver, and Margaret Morrison Carnegie. (The correct pronunciation of the family name is car-NAY-ghee.) The household was socially conscious and historically aware, conducting spirited discussions around the hearth of elections and economics, of the bravery of William Wallace and Robert the Bruce, the humanity of Robert Burns, the historical resonance of Walter Scott, and above all, of the need to make the world a better place. The path to societal improvement, said the Carnegie elders, was radical action. Andrew Carnegie wrote later, “My childhood’s desire was to get to be a man and kill a king.” The comment is as interesting for its personal brio as for its political radicalism. From boyhood, Carnegie was fair-to-bursting with a need to remake the world.

His father William was an activist in the Chartist movement, a crusade by workers against control of Parliament by the aristocracy. Historian Eric Hobsbawm offers a summary of Britain’s working class during Carnegie’s childhood in the 1830s and ’40s: “Luddite and Radical, trade-unionist and utopian-socialist, Democratic and Chartist. At no other period in modern British history have the common people been so persistently, profoundly, and often desperately, dissatisfied.”

America and Canada were outlets for dissatisfied thousands. When William Carnegie lost his job in the late 1840s, the family emigrated to the U.S., settling in a poor section of the Pittsburgh area. Andy soon quit school and plunged cheerfully into the world of work, finding employment in a cotton mill, followed by jobs in telegraphy and railroads. He rose quickly. By 1859, at age 24, he was a divisional superintendent for the Pennsylvania Railroad. He brought intelligence to his work, and imagination, and a vigor that allowed him to move mountains and to irritate the heck out of his co-workers. “Never knowing fatigue myself,” he wrote of his railroad days, “I overworked the men and was not careful enough in considering the limits of human endurance.”

Never knowing fatigue myself. The phrase rings like steel drums through the life of Andrew Carnegie. He possessed as much energy and drive (and ego) as anyone of his time.

When he was in his 20s, Carnegie purchased 10 shares of stock in a blue-chip company called Adams Express, the Federal Express of the day, and soon received a dividend check for $10. This was the first time he’d gotten money from an investment – his first taste of capitalism from the ownership side rather than the laboring – and he announced joyfully, “Eureka! Here’s the goose that lays the golden eggs.”

Serving as a transportation specialist for the Union Army during the Civil War, he invested in oil, coal, and iron ore. A war prosperity was underway. Carl Sandburg, in his biography of Abraham Lincoln, quotes a wealthy Boston merchant of the era: “‘Cheap money makes speculation, rising prices and rapid fortunes.” Andy Carnegie, largely because of stock dividends, earned an income of $42,260 in 1863, at a time when the President of the United States made $25,000 annually. “I’m rich!” announced the one-time poor boy.

Getting money felt good, but chasing the buck was not his chief passion. Deep in his bones was a memory of sitting near the fire as a boy listening to his elders talk of noble and defiant deeds. He articulated his idealism in 1868, at age 33, writing a private note to himself with instructions to quit business within two years, get an education, become a crusading newspaper publisher, and change the world for the better. Further dalliance with filthy lucre, he said, would be degrading. This plan didn’t work out – the money kept pouring in; he couldn’t just walk away from it – but he never forgot the note.

He built his first mill on the outskirts of Pittsburgh in 1875 and filled it with energy and creativity. He was one of the first U.S. industrialists to pay close attention to laboratory research, never hesitating, in the early days, to write checks for technological innovation. Carnegie’s steel became the structural basis of American greatness, the foundation of the nation’s railroads, factories, bridges, and skyscrapers.

His team was talented. His key manager on the mill floor, William “Captain Bill” Jones, was one of the great laboring men of the 19th century, a Shakespeare-quoting Civil War veteran who seemed to savor every moment of his working life, from designing and installing new equipment, to watching molten ingots come forth from the furnaces, to feeling, at the end of the day, that he had well-and-truly earned his pay. He was “seared by the heat,” writes historian Joseph Frazier Wall, “deafened by the noise of metal rolling over metal and nearly blinded by the white, incandescent heat of molten iron,” and he loved it. Inspired by Carnegie, inspired too by the exuberant U.S. building boom of the post-war years, Jones infused his men with a near-religious fervor for creating a new nation; they toiled with gusto, drank cold beer, and started again the next morning.

Danger accompanied their work. Capt. Bill survived the Battles of Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville but was killed in a furnace accident in 1889 at age 50.

Carnegie had a complicated attitude toward his men. On the one hand, he was a proud son of the working class, receptive to certain enlightened policies, such as the steel industry’s first eight-hour day, created by his company in 1877. At the same time, he was lashed by the need to trim costs. This brought out his inner martinet.

In 1892 he approved a plan to destroy a steelworker’s union at his Homestead mill near Pittsburgh. This was in the days before unions were protected by law, when they were regarded by many capitalists as the first wave of socialism, threatening not only profits but the republic. Pinkerton guards opened fire on Homestead strikers in July of 1892; all told, at least 10 people died, including strikers and detectives.

Carnegie hadn’t expected armed conflict and was horrified by it. He was traveling overseas when the shooting broke out, but he was the responsible party. People asked why he out of the country when a troublesome situation was brewing.

He hated the criticism. He wanted to be loved. He dealt with the pain of Homestead by blurring its details in his memory in a way that reduced his culpability. He needed to preserve a sense of himself as an idealist. He had a substantial capacity for illusion about certain topics; this would have major consequences in the last years of his life.

Carnegie’s mother, Margaret, died in November of 1886, and five months later, when he was 51, Carnegie married for the first time, to Louise Whitfield, age 30. The couple had a daughter, Margaret, nicknamed Baba.

An affectionate family man, Carnegie relished retreating with his loved ones to Skibo, their estate in the Scottish Highlands, one of the most gorgeous slices of real estate on the planet, where he could ride horseback, swim, entertain, read, and propel his bouncy five-foot frame across golf courses. He was very good at balancing relaxation with hard work, surely a factor in his good health through the years. (He was “said to sulk” when he didn’t win at golf, reports historian David Nasaw, so perhaps his friends let him win.)

In 1900, with the dawn of a new century, a limitless future seemed to beckon to America. Carnegie was excited about the potential of his steel to bend and shape that future. But once again his divided self asserted itself – he also hankered to become a full-time good-deed-doer.

As it happened, the financier J.P. Morgan wished to acquire Carnegie Steel. He asked Carnegie in 1901 how much he wanted for the company. The reply: $480 million. Morgan said, “I accept this price,” and the deal was more-or-less done. Andrew Carnegie was now the richest man in the world in terms of liquid assets, counting more than $200 million in his personal portfolio. He happily embarked on a new chapter of his life, as spectacular as the first – giving his money away.

Carnegie was not the world’s first major philanthropist, nor America’s, but he was a pioneer in committing himself to giving away most of his fortune while he was alive. He described this radical stance in an 1889 essay. This is the famous article that “most contemporary CEOs would undoubtedly choke on,” writes author George Scialabba. Rich people, Carnegie said, should give away most of their pile in beneficial ways, and if they don’t, they die “disgraced.” The key problem of the industrial era, he continued, is the “proper administration of wealth, so that the ties of brotherhood may still bind together the rich and poor in harmonious relationship” – a precise summary of the problem of income inequality, as large a problem today as in 1889.

He brought a fresh approach to the nuts-and-bolts of giving. He, personally, carefully sifted through requests and identified worthy recipients, rather than allowing others to do the work haphazardly.

One of Carnegie’s first projects was to supply America with libraries that could be used free by anyone. Such establishments were rare when he set to work. He spent more than $50 million on the effort, building 1,946 library buildings in the U.S. Meanwhile he donated bountifully to colleges, universities, museums, and research groups. He gave no-strings endowments and pensions to many people, including teachers and professors. He established the Carnegie Hero Fund Commission in 1904 to recognize and reward heroism in North America; the organization has distributed more than $30 million in benefits and prizes over the years. “It is the fund,” he said, “that may be considered my pet.”

Carnegie’s ego remained formidable. He became, writes David Nasaw, an “all-purpose expert” on how to live, “willing to dispense advice on just about any topic” to people who wrote to him, including members of the public, journalists, and politicians. Someone sent him a letter asking for dietary guidance. In reply, he described his habits as “just in the middle” – some meat but not a lot, and an “abstainer” with liquor except what his doctor ordered. The doctor ordered half a glass of expensive Scotch at lunch and another at dinner, every day without fail; Carnegie cheerfully complied.

He poured time and money into the pursuit of world peace – writing checks, speaking at conferences, conducting correspondence, and, to borrow a phrase from Evelyn Waugh, studying interesting papers about plebiscites in Poland. He believed peace was nigh, that humanity was advancing apace, that progress was swift and sure. In a letter to the New York Times in 1907 (published on page one of the paper) he proclaimed, “The world is growing better….Men are more kindly disposed, more charitable, more solicitous for others, less selfish.” Soon, he said, war will be a “thing of the past. Oh, yes, indeed!” In 1910 he founded the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

In common with many people in the early years of the 20th century, Carnegie believed that world amity would be generated by science and machines, aided by a “league of nations” or “league of peace.” Among the recent events shaping this societal outlook were the airplane flight of the Wright Brothers in 1903, the expansion of radio communications in 1901, the Exposition Universelle of 1900 in Paris, the Hague Convention of 1899, the first modern Olympics in Athens in 1896, and, to reach further back, the Congress of Berlin of 1878, the laying of a successful transatlantic telegraph cable in 1866, and the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London. (The latter event was organized by Prince Albert, entranced, like Carnegie, by the technical miracles of the 19th century.)

Carnegie’s conviction about the coming of peace shows his wonderful optimism and also his ability to close his mind to things he wished to avoid, such as Europe’s seething nationalist tensions, huge standing armies, accelerating arms race, and the conviction of millions of its citizens that war is actually better for humanity than peace – that battle is the source of true progress, deep progress – that a good fight would be a slap of spicy aftershave upon the collective morning face of a generation of coddled young men. This belief in the “regenerating value of violence,” to use a phrase of journalist and historian Geoffrey Wheatcroft – in the “purifying” effects of war, to quote writer Walter Kirn – was fully as widespread in 1900 as hopes for peace.

(Journalist Michael Dirda on the great cosmopolitan Harry Kessler: “Like many others, he initially welcomed [World War I] as an almost mystical struggle….”)

The deification of violence was a decisive underpinning for large swaths of global culture, Western and Eastern, from the 1890s to 1945. It was born of worries about the negative effects of industrialization and bureaucratization, and of vulgar and/or artistic interpretations of Nietzsche and Darwin. In America, key literary figures in this impulse were Jack London and Stephen Crane, and, later, Ernest Hemingway (this, at a time when the novelist was the sovereign of the arts, dictating some significant percentage of the cultural agenda). It helped pave the way for millions of men, women, and children to die violent, painful, and lonely deaths. It affects the present day.

Carnegie, for all of his optimism, was aware of Europe’s fever. But did he grasp the depth of the illness? If he had set aside his pleasant illusions, would he have spent his spectacular sums differently? What if he had fulfilled his ambition to be a newspaper publisher by launching a global paper devoted to reform? An illustrated weekly, let’s say, in several languages. Distributed free to millions of homes. Put on the desk of every major politician. Using the reportage of E.D. Morel, Ida Tarbell, and their ilk to transcend jingoistic journalism, expose the world arms race, and cast light into the dark corners of duplicitous diplomacy. Perhaps a decade of aggressive illusion-free reportage would have made a difference.

As the Great War began in August, 1914, the British statesman Edward Grey watched streetlights being doused in London and offered the most heartbreaking metaphor of modern times: “The lamps are going out all over Europe: we shall not see them lit again in our lifetime.”

Carnegie refused, at first, to believe that the fighting represented a major conflict. Perhaps he took heart from an illusion-saturated article in The Economist in the autumn of ’14 that proclaimed “the economic and financial impossibility of carrying out hostilities many more months on the present scale.” As historian Niall Ferguson notes, financial experts of the era were much influenced by the ideas of Ivan Bloch and Norman Angell, “both of whom had argued that the unprecedented costs of a major war would render it, if not impossibly expensive, then at least brief.” (A passage from Albert Camus comes to mind: “When war breaks out people say: ‘It won’t last, it’s too stupid.’ And war is certainly too stupid, but that doesn’t prevent it from lasting.”)

Carnegie eventually grasped what was happening in Europe, and his spirits sagged grievously into bone-deep fatigue, possibly for the first time in his life, or since the Homestead Strike. He contracted pneumonia and recovered with agonizing slowness. Sitting alone in his garden in New York City for hours on end, he stared into space, “saying nothing,” writes Joseph Frazier Wall, “and showing no interest in anything or anyone.”

“It is impossible from our vantage point,” writes David Nasaw, “to know the cause of Carnegie’s silence….We cannot diagnose Carnegie’s condition.” Maybe so, but we can make a reasonable guess that the war had something to do with it.

Eventually he snapped out of it, finding hope in the peace ideas of President Woodrow Wilson, but the emotional piers of his life – optimism, and belief in steady progress – had been damaged. He died on August 11, 1919, age 83, spared the knowledge of America’s refusal, three months later, to join the League of Nations.

He had given away more than 90 percent of his money. He was, writes George Scialabba, “perhaps the….most generous capitalist of all time.” Today his name lives on in many ways, including beautiful library buildings across America, Carnegie Hall in New York City, Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, and the Carnegie Corporation. And the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, where people do much good, and presumably eschew illusion. ●

This is a Carnegie-financed library in St. Paul, Minnesota, in the St. Anthony Park neighborhood. Carnegie made the grant in 1914 and the library three years later. (This photo was shot during closing hours, hence the gate on the stairway.)