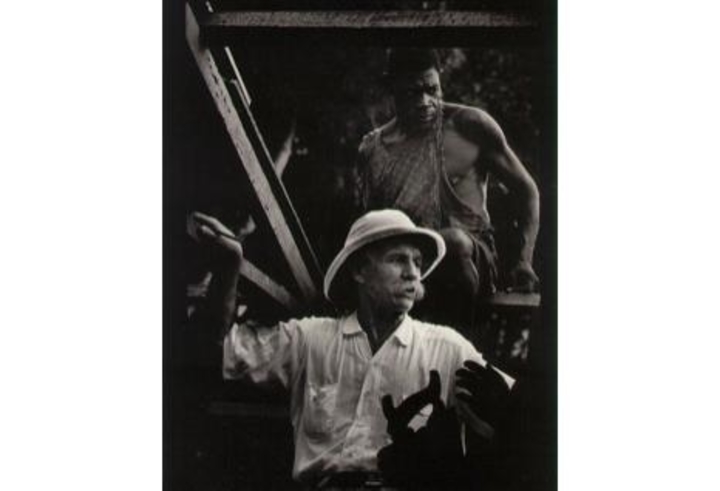

Albert Schweitzer:

The Healer in the Forest

By Harald Frost

Biography magazine, 2001

Albert Schweitzer offered a measure of hope. He won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1952. Preachers cited him in their Sunday sermons. A magazine named him “the world’s greatest living nonpolitical person” and he was the subject in 1957 of an Oscar-winning documentary. Millions of people, of all faiths and creeds, took inspiration from the pith-helmeted Christian missionary laboring in the African forest.

Schweitzer was born in Alsace, a region in central Europe claimed over the centuries by both France and Germany. It was German in 1875, and on January 14th of that year it welcomed a new citizen, the second child of the Rev. and Mrs. Louis Schweitzer.

Albert – “Bery” to his family – spent considerable time as a boy in a sort of dreamy trance, ignoring rote schoolwork and musing on large topics: the beauty of nature, the purpose of prayer, the invisibility of God, and the apparently intractable fact of suffering. As an adolescent, helped by a patient teacher or two, he discovered the value of self-discipline and became an honors student.

One morning in 1896 when he was 21, as he lay in bed pondering his place in the scheme of things, Schweitzer committed his heart and soul to a bracing life plan. He would spend the remainder of his 20s completing his studies, and then create a career that consisted entirely of service to humanity, with little or no remuneration. He wasn’t sure what that service would be, but he felt confident he would find the right path.

By 1900, when he was 25, he had earned a double doctorate, in philosophy and theology, and was a minister in the Lutheran Church. In his spare time he became a virtuoso on the organ and an expert on Johann Sebastian Bach.

Schweitzer completed his theological studies in 1906 at age 31 by publishing a major book in Germany – an intellectual “bombshell” according to scholar Dennis Ingolfsland – “The Quest of the Historical Jesus.” This work, an analysis of 18th and 19th century theories on the life of Christ, created a schism in theological circles that’s discussed and debated to this day. The book caused studies of the historical Jesus to branch into two roads. One, followed by adherents of William Wrede (1859-1906) held that Jesus did not believe himself to be the Messiah; the other, the Schweitzerbahn (Schweitzer’s road), a term coined by scholar N.T. Wright, followed Schweitzer’s belief that Jesus did see himself as the Messiah and died in despair on the cross when he failed to bring God’s kingdom immediately to humanity. (An electronic version of the book can be found here.)

Coming to grips with Jesus, and with Christianity, was the intellectual and emotional task of the first part of Schweitzer’s life. He burrowed into these topics not only to understand them but to help them remain relevant. The modern age, he said, requires more than simple belief. He wrote,

Christianity has need of thought that it may come to the consciousness of its real self. For centuries it treasured the great commandment of love and mercy as traditional truth without recognizing it as a reason for opposing slavery, witch burning, torture, and all the other ancient and medieval forms of inhumanity. It was only when it experienced the influence of the thinking of the Age of Enlightenment that it was stirred into entering the struggle for humanity. The remembrance of this ought to preserve it forever from assuming any air of superiority in comparison with thought….Nowhere does (Jesus) demand of his hearers that they shall sacrifice thinking to believing.

Schweitzer studied Jesus as diligently as anyone of the 20th century and also pondered Nietzsche, Goethe, and many others. Based on his studies he created a model for how to live. This conception featured a reverence for all life (“By practicing reverence for life we become good, deep, and alive….Until he extends his circle of compassion to include all living things, man will not himself find peace.”). He also emphasized a commitment to service – practical, hands-on, difficult, real-world, self-sacrificing, low-paying service. “I don’t know what your destiny will be,” he said to a group of students years later, “but one thing I do know: the only ones among you who will be really happy are those who have sought and found how to serve.”

“It had become rooted in his mind,” writes James Brabazon, Schweitzer’s best biographer, “that if he wanted to achieve his potential – the greatness that Nietzsche and Jesus asked for – it could only be at the cost of some sacrifice.”

This core fact was accompanied by several others:

* He was by nature idealistic and altruistic.

* He was a loner who needed to do things his way.

* His energy level, said one observer, was “superhuman”; he possessed the sheer physical health and strength to engage in a demanding task.

* From a political standpoint he was attracted to the idea of paying back some of the damage done to African countries by European colonialism.

Following the words of Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount, Schweitzer turned away from material gain, from money and honors, from ego gratification, from a beautiful future home in the Alsergrund neighborhood of Vienna and the gooey-eyed admiration of students following him into lecture halls. He decided to become a medical doctor and offer service to the poor.

A phrase comes to mind, a description of St. Francis of Assisi by historian Kenneth Clark: “(He believed) that in order to free the spirit we must shed all our earthly goods….(This) is the belief that all great religious teachers have had in common – eastern and western, without exception. It is an ideal to which, however impossible it may be in practice, the finest spirits will always return.” And as philosopher Roger Scruton writes, “Happiness does not come from the pursuit of pleasure, nor is it guaranteed by freedom. It comes from sacrifice: this is the great message that all the memorable works of our culture convey.”

Schweitzer enrolled in medical school in Strasbourg and in 1912 was granted an M.D. He was accepted by a Christian missionary organization, and in 1913, age 38, he departed France on a south-bound steamer, accompanied by his new wife, Helene, a trained nurse. A few weeks later they arrived at the village of Lambarene, on the Ogowe (Ogooue) River, in a region of French Equatorial Africa that later became the nation of Gabon.

This was one of the most primitive rainforests on earth. The climate on many days featured a damp, suffocating heat that sapped the life out of people. Insects were a scourge. The local diet was abysmal. Superstition and fetish were rife, and untreated injuries, pain, and disease were pervasive. “Here among us everybody is ill,” said one local resident. Within hours of the arrival of the Schweitzers, local folk appeared in the clearing in search of care – people with skin diseases, malaria, leprosy, heart ailments, dysentery, bone injuries, hernias, tuberculosis, and many other afflictions. Albert and Helene set to work.

The hospital was the center of Schweitzer’s life for the next half-century.

Helene was forced to retreat to Europe because of her precarious health, which made work in that climate impossible. She remained in northern climes for most of their marriage, raising their daughter, Rhena.

Schweitzer took occasional breaks, voluntary and otherwise, including a stretch from 1917 to 1924 when he was kept in Europe by ramifications of the First World War and other reasons. He returned to Lambarene in April, 1924, and started over. He visited Europe frequently thereafter to visit his family, recharge his batteries, and raise money.

Modest fame came his way in the early 1920s when he published a book titled “On the Edge of the Primeval Forest.” In 1947 Life magazine gave him a memorable headline: “The Greatest Man in the World – That Is What Some People Call Albert Schweitzer, Jungle Philosopher.” Time magazine put the doctor on its cover in 1949. The Schweitzer legend reached a peak in 1952 when he won the Nobel Peace Prize.

Meanwhile the hospital grew, attracting a steady stream of volunteer doctors and nurses.

When these fervent young professionals arrived in Lambarene, they learned a surprising fact. Schweitzer, while profoundly religious, was no saint. Or, better put, he was as human as many a saint.

He had a problematic attitude toward some of his African employees, stemming from his belief that they were not always prompt. He recognized the deeper reasons for the apparent tardiness – the climate, and the fact that the locals had no tradition of advancing their lives by the getting of money – but he had a hospital to run. Sometimes he bellowed angrily at workers, and on a few occasions he slapped or hit them. He kept himself apart from them, declining to share their lives, in the interest of creating an aura of paternalistic authority. He didn’t see any other way to get things done.

The paternalism was silly and the slapping was wrong.

Journalist John Gunther offered a description of the doctor in the 1950s: “August and good….but cranky on occasion, dictatorial, prejudiced, pedantic in a peculiarly teutonic manner, irascible, and somewhat vain.” Fair enough. Two facts should be added: (1) Schweitzer was loved by the people of the region. (2) He did more day-to-day work to help poverty-stricken Africans achieve health and well-being than any other white person of his time.

For 41 years, from 1924 to 1965, most of the days of Albert Schweitzer followed a rigid routine.

With the wake-up gong at 6:45 a.m., doctors and nurses began visiting patients in the wards, assessing overnight changes. Breakfast was served at 7:30, and soon thereafter, new patients gathered near the consulting room, waiting for the door to open. Surgeries were usually performed in the morning. The quality of care was generally high, many observers report. The relief of pain was a priority. “Pain,” Schweitzer declared, “is a more terrible lord of mankind than even death himself.”

Every morning a group of men headed into the forest to cut firewood. Throughout the day, nurses changed linen, sterilized instruments, supervised housekeeping, kept records, offered comfort, and did the thousand tasks that nurses do. Washerwomen labored, and cooks baked loaves of thick, chewy bread.

Gardens and livestock received attention. Poisonous snakes were ferreted out. Trees were planted, and structural damage (inflicted by insects, heat, and humidity) was fixed. All of this was done in a climate where, Schweitzer estimated, “one can only get through three-fifths of the work of which one is capable in Europe” – 60 percent of what he could do in Vienna – surely a vexation to a man who had committed himself to giving 100 percent to life.

Still, the hospital atmosphere was not oppressive. True, the heat was awful and the boss was a grouch now and then – “the old idiot,” he sometimes called himself – but he usually created a mood that combined seriousness with light-heartedness and fun. Without such a spirit, work would have been impossible.

After the mid-day meal at 12:30 p.m. the doctors and nurses were ordered to rest. At 2 p.m. consultations resumed, continuing until the evening bell at 6. And so it went, seven days a week, 365 days a year, year after year.

After the evening meal, Schweitzer often played Bach on his custom-made piano/organ, a beautiful instrument built to withstand the tropics. He read and wrote until late. He had a huge correspondence load including a campaign against nuclear weapons. On Sundays he conducted a church service.

After dark, a silence descended on the camp, lasting for about half an hour, until the forest erupted in a cacophony of cicadas and toads, which continued for several hours.

Peace reigned in the hours before sunrise. The palm trees rustled, and the air, on occasion, was mild and fragrant. Perhaps, while listening to the wind in the trees, Schweitzer allowed himself a moment of satisfaction, thinking about his day’s work, his life’s work, and about the millions of people around the world inspired by his passion and reverence.

Albert Schweitzer died in Lambarene at age 90 on September 4, 1965, and was buried in the banks of the Ogowe River. The hospital complex by this time had 70 buildings. The work continues today, and the palm trees rustle over the good doctor’s grave. ●